My Vision Diagnosis

Oculomotor Dysfunction (Eye Tracking Problems)

In order for eyes to work efficiently, they must be able to follow moving objects (pursuit movements), and be able to jump from one object to another (saccadic eye movements). Proper eye movement skills are needed for reading and writing so that eyes move voluntarily with speed and accuracy. “Oculomotor dysfunction” is the ophthalmic terminology for reduced eye movement skills.

People with inadequate eye movement skills lose their place, skip words or lines while reading, omit words or letters when reading or writing, and reverse words or letters. Often “slow readers” or children with academic disabilities have poor eye movement skills. Symptoms include headaches, blurred or double vision, dizziness, and eye fatigue. Occasionally, neurological conditions such as a stroke can affect eye movement skills.

Children with Oculomotor Dysfunction may avoid visual frustrations by refusing to participate in classroom lessons and resort to day dreaming or distracting themselves and others. They are frequently identified as strong auditory learners and may be misdiagnosed with ADD, ADHD, dyslexia, and other learning disabilities.

Children and individuals with neurological conditions cannot overcome these functional conditions without help. Academics, behavior and athletic achievement can all be affected by the quality of eye movements. Treatment includes specially prescribed visual therapy eye techniques that develop the control of eye movements.

Good Reading Skills

Paul likes to take his blue toy truck to the playground and share it with his friends.

Deficit in Eye tracking Skills

paulik esto take his blue toy truck tothe playgrounda ndshare it withhis friends.

Accommodative Dysfunction

People with “normal” vision are able to use each eye independently, and both eyes together, to quickly bring objects of visual interest into sharp focus. This is accomplished subconsciously, rapidly, creating no stress on the normal visual system.

For example, if you were reading a book and heard something outside, you might look out the window. Although you moved your eyes from a close-up task to a distance object, your eyes automatically focus on the new image outside the window.

For people with focusing problems, the eyes do not focus properly. The focusing system may be over or underactive, resulting in the inability to see clearly when changing gaze from near to far or far to near; eyes may experience eye strain after only a short time.

In a classroom setting children will try to bring words on a page into focus and may succeed. However, when they look up at the blackboard, it may appear fuzzy. When they return to looking at the book, they must devote a lot of energy to refocus the words in the text. This accommodative dysfunction causes eyestrain, headaches, and difficulty concentrating.

Children with accommodative dysfunction avoid reading, dislike copying from blackboard to paper, and are sometimes misdiagnosed with ADD, ADHD, dyslexia, and/or other learning disabilities. Focusing and eye teaming skills work in combination with each other, and lack of skills in these areas are extremely frustrating to parents. The child appears bright but struggles in school. The child doesn’t want to read but has no problem playing video games or being read to. Parents may assume the child is not putting forth effort, is lazy or is not paying attention.

Vision therapy is required to properly treat accommodative dysfunction by teaching the eyes to change focus comfortably for extended periods of time and see clearly quickly when changing viewing distances. The treatment uses lenses and instruments to develop these skills.

Eye Teaming Problems, Convergence Insufficiency and Convergence Excess

Our two eyes capture separate images and send them to the brain’s visual cortex to be processed in order to get one unified, or fused, final image. Good eye teaming, or binocular, vision allows sustained, single comfortable vision and is the basis for depth perception or the 3D view of the world.

For some people, aiming their eyes at a close distance requires extensive effort because the eyes may not have developed the ability to work well together or they may be slightly misaligned. Convergence Insufficiency describes when the two eyes cannot come together comfortably and efficiently to view an object close up or during reading or close task activities. Convergence Excess is when the eyes have a strong tendency to turn in during reading and close work.

In both cases individuals must work to keep their eyes pointed at the same place; such effort often results in double or blurred vision and headaches. When individuals must work hard just to keep their eyes together, comprehension decreases because such effort causes blurring, jumping and splitting apart, making it more difficult to perform near-point work comfortably for extended periods of time.

This inability of the eyes to work together affects 10-20% of individuals. Neither of these problems is detectable when just looking at a child and is often undiagnosed because while eyes are frequently evaluated individually, they are rarely assessed for how well they work together.

Vision Therapy is the only way to treat all eye teaming problems. The program uses combination of lenses, prisms, instruments, specialized computer programs, and variable demand 3-D techniques to expand the range, accuracy, speed and the development of adequate compensation for this eye muscle imbalance.

This inability of the eyes to work together affects 10-20% of individuals. Neither of these problems is detectable when just looking at a child and is often undiagnosed because while eyes are frequently evaluated individually, they are rarely assessed for how well they work together.

Vision Therapy is the only way to treat all eye teaming problems. The program uses combination of lenses, prisms, instruments, specialized computer programs, and variable demand 3-D techniques to expand the range, accuracy, speed and the development of adequate compensation for this eye muscle imbalance.

Visual Perceptual Problems (Visual Information Processing)

Perception is the ability of the brain to interpret information through various motor and sensory systems. Visual perception, or visual processing, is the ability of the brain to analyze and interpret information through the eyes and visual system. The process is complex and depends upon the quality of the data coming through the visual system to the brain as well as the ability of the brain to interpret this information.

Number and letter recognition, early reading and math skills, handwriting, and the ability to copy and organize written work all depend on good visual processing ability.

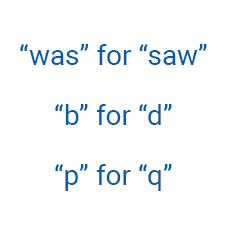

Deficiencies in clear sight, eye tracking (fixations and saccades), eye focusing ability, and eye teaming affect visual perception. In most children visual processing develops normally as an outgrowth of normal development and environmental experiences during early childhood along with other complicated neurological and physiological processes. In some children, however, the development of visual processing skills does not keep pace with their growth. When visual processing is delayed, problems such as difficulties telling left from right, word/letter reversal (“was for saw,” or “b” for “d,”), clumsy behaviors and problems with math concepts may result.

80% of information is gathered through the visual system, and efficient and effective learning and problem solving require a “normal” visual perceptual system. Perceptual problems may produce identical symptoms as dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD.

Dr. Newman uses a battery of tests to evaluate visual components of visual perception to determine if the visual information processing is adequate.

Types of Visual Processing Problems:

Directionality: ability to know left from right, especially as it relates to letters and numbers

Visual form perception: ability to detect likes and differences in shapes, letters, numbers and words

Visual memory: ability to recall visually presented information

Visual motor integration (eye-hand coordination): ability to combine visual information with motor output.

Visual processing speed: Ability to process visual information quickly and accurately.

Signs of a Visual Processing Problem

- Reversal of letters, numbers or words when writing or copying

- Difficulty learning left and right

- Lack of coordination and balance

- Poor athletic performance

- Sloppy handwriting, poor spacing of letters, inability to write on a line

- Can respond orally but unable to produce answers in writing/li>

- Erases excessively/li>

- Messy drawing or writing skills/li>

- Difficulty copying from the board/li>

- Better auditory learner/li>

- Poor attention during visual tasks/li>

- Poor retention of visual material (sight words)/li>

- Unable to recognize same word repeated on a page/li>

- Difficulty completing written assignments in allotted period of time/li>

- Difficulty with scantron answer sheets/li>

- Difficulty writing numbers in columns for math problems/li>

- Overwhelmed with crowded pages or worksheets/li>

- Poor fine or gross motor skills

Amblyopia (Lazy Eye)

While amblyopia is often described as a lazy eye, a more accurate description is that the brain has a preference for one eye over the other, which may result in the unfavored eye turning in or out. If the non-preferred eye is blurred or obstructed, the brain has difficulty accurately fusing the images from both eyes. As a result, the brain adjusts to rely solely on information that comes from the clear, unobstructed eye.

In order to facilitate vision, the brain literally blocks the images from the unfavored eye and refuses to process any images from it; the eye is essentially “turned off.” Once the eye is “turned off” the brain no longer needs to work to organize the visual information that eye provides and can depend solely on the other eye for all its cues. The eye that is turned does not have normal visual acuity, for the brain accustoms itself to using only one eye. Subsequently, the non-preferred eye may have very poor vision and must be retrained in order to team with the other eye. Often vision therapy helps equalize the eyes, improving the brain’s ability to fuse the two images into a single 3-D picture.

Strabismus (Crossed Eyes)

Strabismus, often referred to as “crossed eyes” or “wandering eye,” refers to the brain’s inability to properly align the eyes and results in the eyes turning in, out, up, or down. This may occur part time or all the time. With normal vision, each eye is aligned and therefore capable of pointing at the same precise point in space. This allows the brain to see two different, but similar, pictures that it puts together to produce a single 3-D image.

However, an individual with strabismus has eyes that are misaligned and are therefore unable to point at the same place. Consequently, the brain receives two separate pictures, which it cannot adequately combine. At first this may result new1in double vision, but the brain eventually will turn off the eye that is misaligned to avoid the stress of trying to fuse the two disparate images. As the brain becomes dependent on only one eye for all of its visual information, an individual loses 3-D vision, and the eye that is turned remains undeveloped.

Two basic approaches can correct an eye turn. One involves vision therapy and the other surgery. In certain cases, a combination of vision therapy and surgery is needed. Vision therapy involves a treatment plan designed to eliminate the eye turn, but the goal of a vision therapy program goes beyond straightening the eyes. The patient learns to more effectively utilize and integrate the information seen with each eye in a more coordinated and efficient manner.

The outcome of a vision therapy program can be both cosmetic (straight eyes), as well as a functional (proper visual skills). The outcome of surgery is more often cosmetic than functional. When deciding which type of treatment to pursue, it would be best to treat both the cosmetic AND the functional vision aspects. Vision therapy may be initiated both before and after surgery to help a patient use both eyes together.

Loss of 3D (Stereo-Vision)

The two eyes deliver two slightly different images to the brain. The brain then compiles these two images into one single 3-D reality. The two images are combined by a process called “visual processing.” We are able to see objects more than just flat or long; instead we have three-dimensions—width, height and depth. This type of viewing is called stereo-vision, deriving from the Greek root “stereos,” meaning firm or solid.

However, not everyone’s brain can automatically fuse the two images, and sometimes a slight misalignment of the eyes or a traumatic brain injury can make it difficult for the brain to make sense of the separate images from each eye. This results in a loss or lack of stereovision. Some people are not even aware that they do not see the world in 3-D because their brain has never been able to compile the two images and relied only on one preferred eye for all its visual information. Although some individuals adjust to life without stereo-vision and have developed a way of interpreting objects in space, they have a more difficult time with everyday activities such as throwing or catching a ball, driving a car, or stepping off a curb.

Our Location

Our Address

- 8314 Wishire Blvd, Ste A

- Beverly Hills, CA 90211

Contact Us

- Phone: 323 653 4078

- Email: [email protected]

Clinic Hours

- Monday: 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

- Tuesday: 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

- Wednesday: 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

- Thursday: 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

- Friday: 10:00 AM – 5:00 PM

- Saturday: Closed

- Sunday: Closed

Our Brands

Our Google Reviews

Knowledgeable

Friendly

Caring